Share your perspective and help improve the health of our community! We are conducting a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) to help us better understand the health needs of the community our health system serves. Learn more and take the short survey.

Latent Tuberculosis Infections (LTBI)

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by inhalation of the atypical organism Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) and may progress to either active symptomatic disease or latent immunologic containment. The clinical manifestations and hallmark of active “symptomatic” TB includes a cough >2 weeks' duration, fevers, night sweats and weight loss. Most individuals, however, don’t immediately develop these symptoms. A quarter of the world’s population has been exposed to MTB and many of these individuals may continue to harbor the bacterium in a latency state only to re-activate later when immunity can wax and wane. This article identifies those patients with latent tuberculosis (LTBI) who are at high risk of progression to active disease and outlines the testing and treatment that can significantly reduce the risk of developing fulminant TB disease.

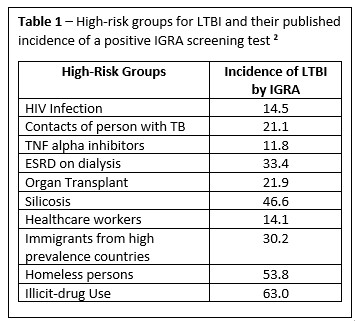

The prevalence of TB is highest in regions of South-East Asia, Africa and the Western Pacific where 80% of the population tests positive for MTB. By contrast, it is estimated that 5-10% of the United States’ population has a positive test for tuberculosis. Because of this wide disparity in the prevalence of latent disease, screening is only recommended for those who would benefit from LTBI treatment. There are two broad categories of individuals who should be screened, 1) persons at high risk of a new exposures, and 2) persons who are at increased risk of reactivation due to immunosuppression (table 1). Individuals with LTBI at highest risk for reactivation due to suppression of cellular immunity include HIV, the use of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors or glucocorticoids, and transplantation.

There is no test that definitively establishes a diagnosis of LTBI. As such, LTBI is a clinical diagnosis which is defined by the evidence of a high-risk TB exposure and by detecting a memory T-cell response to M. tuberculosis antigens. There are two widely used tests available to measure immune sensitization (type IV or delayed-type hypersensitivity) following an exposure to MTB. These tests include the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs). The decision to select one of these tests is generally based on the setting, cost and availability. We often use the blood-based IGRA (i.e. Quantiferon) for patients who are unlikely to return to have the TST read and for patients with a history of receiving the bacilli Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine. For those individuals who have a positive immunological response to MTB antigens, and prior to initiation of treatment for LTBI, active disease should be excluded by the absence of symptoms and documentation of normal appearing chest imaging.

Finally, when making the decision to treat individuals with LTBI and those who are at high risk of conversion to active TB, there are several therapeutic options available:

1. Isoniazid 5 mg/kg/day PO (maximum 300 mg/day) x 9 months

a. Add pyridoxine (25 – 50 mg/day) to prevent polyneuropathy

b. Monitor for hepatic toxicity

c. Advise against alcohol use

2. Rifampin 600 mg/day PO x 4 months

a. Monitor for Drug-Drug Interactions

3. Isoniazid 900 mg + Rifapentine 900 mg in 12 once-weekly doses

Although the indirect immunologic screening tests will remain positive for life, the successful completion of LTBI treatment can reduce the development of active TB disease in high risk individuals by more than 90 percent. Please consult your Infectious Disease clinic if you need assistance for the management and prevention of high risk LTBI.

References:

1. ATS/IDSA Guidelines: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200:e93-142

2. New Eng J Med. 2015; 372:2127

3. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2020; 34:413

4. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:1670